Details of the world’s first successful use of mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT) in IVF have been published.

Although the birth of a healthy baby to a mother carrying the mitochondrial mutation for Leigh Syndrome was announced in the press last year, the scientific details had not been revealed until now, and have raised both positive reactions and concerns from experts.

‘[This study] is one of those rare cases where both the scientific and legal details needed to be in place near simultaneously to make the treatment possible. The bigger picture however is that diseases such as Leigh Syndrome are severely debilitating for the affected children and devastating for the families involved’, commented Darren Griffin, professor of genetics at the University of Kent, who was not involved in the study.

‘Having the ability to give hope to these families is incredibly important and no doubt the first of many treatments of its kind.’

The procedure, led by Dr John Zhang, CEO of the New Hope Fertility Center in New York City, marked the first time that a healthy baby has been born to a mother affected by a heritable mitochondrial disorder as a result of MRT.

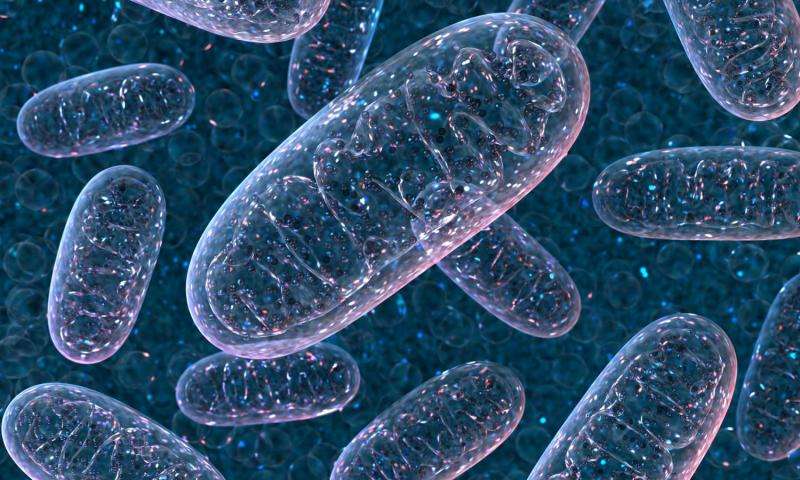

The scientific paper and an accompanying editorial, published in the journal Reproductive BioMedicine Online, describes and comments on the procedure, which combined an enucleated donor egg containing healthy mitochondria with nuclear material from an egg from a carrier of Leigh Syndrome – a fatal neurological disorder caused by a mutation in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

Whether the mother was aware of the risks associated with the procedure is not clear. The paper shows that the consent form signed by the mother did not list the specific risks of mitochondrial replacement, although the parents received ‘cautious counselling for mitochondrial replacement therapy’. The parents have refused further medical monitoring of the child unless there is a medical need.

The severity of Leigh Syndrome is determined by the percentage of affected mitochondria – the ‘mutation load’ – with a threshold of 60 percent load manifesting in disease symptoms. The mother has a mutation load of 24.5 percent, and is asymptomatic. A small percentage of mutated mitochondria was inadvertently transferred through the procedure, and the baby had a mutation load at birth ranging from 2.36 percent to 9.23 percent across different tissue samples.

This is perhaps higher than would be expected following mitochondrial replacement, and there is concern that this may change over the course of the child’s life.

‘It might not be unreasonable to consider this as an experiment; an experiment which uses a child. A child who had no ability to consent,’ said Dr David Clancy of Lancaster University.

Experts have also questioned the technique used to transfer nuclei to the donor eggs and the high abnormality rate of the fertilised eggs. Of the four fertilised donor eggs, only one developed normally to be implanted.

Whilst all initial embryo development was carried out at a private fertility clinic in New York, implantation itself was carried out in Mexico to avoid US federal regulations. A recent paper published in the Journal of Law and the Biosciences suggests the procedure could have breached federal regulations in Mexico, depending on the interpretation of the law.